by Olin Strader and Alison Weisburger Recently one of my colleagues aptly suggested that an Arctic Coast Guard Forum is needed to enhance Arctic security and cooperation. Her comment was made in response to my article calling for an Arctic Council Security Agreement. I couldn’t agree with her more. But I would also suggest that both of these concepts must leverage Arctic indigenous peoples’, indigenous knowledge. This article will focus on channeling indigenous knowledge and political organization into a comprehensive security architecture.

In Tasmaniaʼs capital city Hobart, a plaque in the town square memorializes Sir John Franklin in a poem written by Lord Alfred Tennyson. The poem reads:

Not here! The white north hath thy bones and thou

Heroic sailor soul

Art passing on thine happier voyage now

Toward no earthly pole

What caused the 1846 Franklin expedition to fail and the 1903-1906 Amundsen expedition to succeed? While it is true Amundsen utilized a unique ship design, the primary answer was a reliance on indigenous knowledge. Sir John Franklin’s 1846 Arctic expedition ended in disaster.[1] Arctic archeologists and historians continue to scour the Arctic for clues to the disappearance of Sir John Franklin’s expedition. However, Roald Amundsen is lauded as the man who conquered the North.[2] Both men had extensive Arctic experience. Franklin had taken part in three previous Arctic expeditions, while Amundsen had wintered over in Antarctica prior to successfully navigating the Northwest Passage. Today, those who live below the Arctic Circle are generally ill-equipped to operate and survive in the Arctic without leveraging expertise of Arctic indigenous peoples.

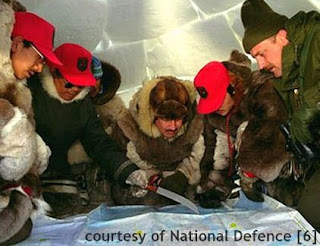

Canada has a model for incorporating Arctic indigenous peoples’ knowledge into their Arctic operations. The Canadian Rangers are a locally and regionally based, Arctic indigenous peoples’ security force who “provide patrols and detachments for employment on national-security and public-safety missions in those sparsely settled northern, coastal and isolated areas of Canada which can not conveniently or economically be covered by other elements or components of the Canadian Forces.”[3] The importance of the Canadian Rangers capability is their potential to access areas not conveniently or economically covered by southern-based Canadian Forces. It is the Canadian Rangers ability to employ traditional and modern means in one of the planets harshest environments to provide safety and security in Canada’s North that makes them invaluable.

The authors of this article believe the Canadian Rangers represent a model that should be replicated around the Arctic basin; a model that could serve to strengthen political and ancestral bonds of nations such as the Inuit, Aleuts, Yupiks, the Samii, Laplanders, the Kalaallit and others around the region, while providing forward security for a rapidly changing Arctic. By encouraging Arctic indigenous peoples to take the lead in securing their traditional lands as partners with their Arctic state security services, they can have a stake in how security is provided. Alternately, as the Arctic changes, Arctic indigenous peoples can assist southerners in making sense of changes in the environment and the accompanying hazards. All around the Arctic Circle indigenous peoples, employing indigenous knowledge could provide forward security and safety from Russia, to the United States, Canada to Greenland, Norway to Sweden and Finland and back to Russia.

The means by which Arctic indigenous peoples’ voices are heard today in international affairs is through political organization. Indigenous peoples of the Arctic have self-organized politically as the Permanent Participants to the Arctic Council, the Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), the Samii Council, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) and other circumpolar organizations. Today, these same politically-empowered, Arctic indigenous people account for one-eighth of the Arctic’s population of approximately 4 million, a sizable population by any calculation.[5]

The Arctic indigenous peoples of the region have over generations acquired specific traditional knowledge that allows them, despite the harsh climate of the Arctic, to call the region home. This same knowledge, knowledge that helped Amundsen and his crew survive the Arctic’s harsh winters and helps the Canadian Forces today, could be useful to Arctic states’ Coast Guards and defense establishments. As an Alaska-based Coast Guard colleague once suggested to this author, the North Slope Inupaiq could be organized into a Coast Guard auxiliary in support of the Coast Guard’s maritime security and safety missions. A North Slope Coast Guard Auxiliary could then link in with the Canadian Rangers, and the Rangers could link in with the Kalaallit of Greenland. The North Slope Coast Guard Auxiliary could theoretically link in with their Serbian Yupik and Aleut relatives, were they to be employed by the Federal Security Bureau’s, Border Guards. The whole Arctic could, in theory, be ringed by Arctic indigenous peoples providing forward security and safety in the Arctic.

The essential point of all this is leveraging the power of the personal, familial and political ties of Arctic indigenous peoples. Arctic indigenous peoples could represent a critical component of Arctic security because of their personal and political investment in its future. The key component to this arrangement is the benefit it represents to Arctic indigenous communities, providing a meaningful way for them to strengthen their own communities and protect the natural habitat. It provides more positive leadership and role modeling opportunities at home for the next generation of indigenous leaders.

The presence of an indigenous circumpolar security force would foster a much greater sense of cooperation in the Arctic than the ever-present sense that there is the potential for conflict (whether realistic or not) that seems to plague nation-state cooperation in the region. It is worth bearing out that Arctic indigenous peoples are not subject to many of the political pressures, complex patterns of interaction, complicated multi-faceted relationships faced by Arctic states. Organizationally, it is much easier for the ICC and RAIPON to cooperate than it is for, say, Arctic states.

It is a logical next step for the Arctic Council to serve as a vehicle to foster indigenous knowledge and address security challenges. Search and rescue could be something an indigenous peoples' force could excel at, given the right parameters and resources. It would seem logical to combine Arctic Council priorities of indigenous peoples’ participation and search & rescue into one very effective program. Additionally, Arctic indigenous peoples could also play a key role in spill response. Indigenous communities along the coast of Alaska are reported to be regularly trained and equipped by the US Coast Guard to employ spill response capabilities. Would it not be advisable to equip all Arctic indigenous communities with this type of capability?

In conclusion, Arctic indigenous peoples are best suited to serve as forward security and safety in the Arctic. When connected by their political and ancestral ties they represent a powerfully connected community of interest. Because of these powerful bonds, Arctic Council member states should strongly consider ways to leverage Arctic indigenous peoples’ indigenous knowledge and channel it into a comprehensive Arctic security and safety architecture.

The Arctic indigenous peoples of the region have over generations acquired specific traditional knowledge that allows them, despite the harsh climate of the Arctic, to call the region home. This same knowledge, knowledge that helped Amundsen and his crew survive the Arctic’s harsh winters and helps the Canadian Forces today, could be useful to Arctic states’ Coast Guards and defense establishments. As an Alaska-based Coast Guard colleague once suggested to this author, the North Slope Inupaiq could be organized into a Coast Guard auxiliary in support of the Coast Guard’s maritime security and safety missions. A North Slope Coast Guard Auxiliary could then link in with the Canadian Rangers, and the Rangers could link in with the Kalaallit of Greenland. The North Slope Coast Guard Auxiliary could theoretically link in with their Serbian Yupik and Aleut relatives, were they to be employed by the Federal Security Bureau’s, Border Guards. The whole Arctic could, in theory, be ringed by Arctic indigenous peoples providing forward security and safety in the Arctic.

The essential point of all this is leveraging the power of the personal, familial and political ties of Arctic indigenous peoples. Arctic indigenous peoples could represent a critical component of Arctic security because of their personal and political investment in its future. The key component to this arrangement is the benefit it represents to Arctic indigenous communities, providing a meaningful way for them to strengthen their own communities and protect the natural habitat. It provides more positive leadership and role modeling opportunities at home for the next generation of indigenous leaders.

The presence of an indigenous circumpolar security force would foster a much greater sense of cooperation in the Arctic than the ever-present sense that there is the potential for conflict (whether realistic or not) that seems to plague nation-state cooperation in the region. It is worth bearing out that Arctic indigenous peoples are not subject to many of the political pressures, complex patterns of interaction, complicated multi-faceted relationships faced by Arctic states. Organizationally, it is much easier for the ICC and RAIPON to cooperate than it is for, say, Arctic states.

It is a logical next step for the Arctic Council to serve as a vehicle to foster indigenous knowledge and address security challenges. Search and rescue could be something an indigenous peoples' force could excel at, given the right parameters and resources. It would seem logical to combine Arctic Council priorities of indigenous peoples’ participation and search & rescue into one very effective program. Additionally, Arctic indigenous peoples could also play a key role in spill response. Indigenous communities along the coast of Alaska are reported to be regularly trained and equipped by the US Coast Guard to employ spill response capabilities. Would it not be advisable to equip all Arctic indigenous communities with this type of capability?

In conclusion, Arctic indigenous peoples are best suited to serve as forward security and safety in the Arctic. When connected by their political and ancestral ties they represent a powerfully connected community of interest. Because of these powerful bonds, Arctic Council member states should strongly consider ways to leverage Arctic indigenous peoples’ indigenous knowledge and channel it into a comprehensive Arctic security and safety architecture.

Sources:

[1] Wikipedia, “John Franklin”, accessed at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Franklin

[2] Wikipedia, “Roald Amundsen”, accessed at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roald_Amundsen

[3] Canadian National Defence and the Canadian Forces, “Canadian Rangers”, accessed at: http://www.army.forces.gc.ca/land-terre/cr-rc/index-eng.asp

[4] Norwegian Polar Institute, “Permanent Representatives of the Arctic Council Map”, accessed at: http://www.polarconservation.org/education/arctic-peoples/arctic-council/permanent-representatives-of-the- arctic-council-map/image_view_fullscreen

[5] The Arctic Council, “Permanent Representatives”, access at: http://www.arctic-council.org/index.php/en/ about-us/permanentparticipants

[6] National Defence, “Canadian Rangers Photos”, accessed at: http://www.army.forces.gc.ca/land-terre/ images/reserve/rangers/gallery/intigloo_b.jpg